Sarah Kwong

‘The most common way people give up their power is by thinking they don't have any.’

ISSUE 12

AUGUST 2022

Dear Reader,

Lately we’ve been wondering: how can we find balance in a world so off-kilter? One way could be to limit our consumption of news. Another might be to explore the quote on this issue’s cover, by author Alice Walker. It’s no easy feat when we’re faced with an endless stream of devastation, but perhaps we can try to shift our focus; there are a lot of things we can’t change, but there are also a lot of things we can change, on an individual and collective level.

An integral tenet of Buddhism is accepting reality for what it is. This can easily be confused for giving up on trying to change things, but perhaps the intended meaning is: you have to accept reality in order to make change. Even though we are frustrated, dissatisfied, and horrified, maybe we need to accept that this is where we’re at so we can take the most effective action.

Yours,

Fellow humans

Cover image: Tai O, Hong Kong, being

Cover quote: Alice Walker

G O O D S T U F F

Travel the world (from home)

Maptia is a volunteer-run website offering interesting stories from around the globe. It’s a collaborative project in which photographers, writers, and general adventurers capture the world and share their findings. The stories are categorised by country, which is perfect for feeding any recent locational obsessions. You can also sign up to embark on ‘mini adventures’ in particular topics (e.g. conservation, tradition, cities, landscapes, etc). You’ll receive one story from that category in your inbox every day for a week.

Listen

“This Hell” by Rina Sawayama confronts homophobes who use religion to inform their prejudice. While the subject itself is serious, Sawayama turns their antagonism upside down with a buoyant pop melody and fierce tongue-in-cheek lyrics (turns out I’m going to hell if I keep being myself / don’t know what I did but they seem pretty mad about it / God hates us? Alright then / got my invitation to eternal damnation). At the heart of the song, though, is the power of solidarity and self-acceptance.

Read, learn, celebrate

On the 9th of this month, we’ll be observing International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. There are tons of fantastic books out there both about and by Indigenous peoples. We’re big fans of Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s memoir-cum-guide to living harmoniously with nature; 2018 novel There There by Tommy Orange; and Ceremony, Leslie Marmon Silko’s 1977 fictional classic about a WWII war veteran.

N O T E S O N

Salt

Our relationship with salt began with salt licks, natural spots where salt deposits are found. Animals can detect them from miles away, and so early humans used the trails animals made to hunt and, later, build roads and settlements. When our diets shifted from meat to cereals, we needed more salt. Underground deposits were hard to access and thus, salt became more desirable and valuable (it was known as ‘white gold’ during the Middle Ages).

Salt, used as a preservative, seasoning, and antiseptic, was traded across Africa and Europe, and people travelled to Istanbul to exchange it for Asian spices. It was traded with gold, and in Ethiopia, salt slabs were used as currency up until the end of the 1800s. In Roman times, Pliny the Elder said that the Latin word for salary (salarium) came from the word for salt (salarius), as soldiers were paid partly in salt (but there’s no evidence for this).

Salt taxes, however, definitely existed. In France, citizens had to buy their salt from royal storehouses (their anger about the high tax later helped spark the French Revolution). In the 1930s, Gandi famously led a mass pilgrimage to the seaside to protest the extortionate British tax on salt in India.

Salt also affected beliefs. Where you sat in relation to the saltcellar on a banquet table determined your status (sitting at the head meant you were ‘above the salt’). The custom of throwing salt over the left shoulder after spilling it came from the idea that the devil loitered on the left. In da Vinci’s The Last Supper, an overturned saltcellar is in front of mardy Judas.

Today, we still primarily use salt in food. Humans need sodium to maintain the body’s fluids and muscles. In fact, salt is so integral to our physical processes that adult bodies contain about three saltshakers’ worth of the stuff!

A L B U M S F O R W H E N E V E R

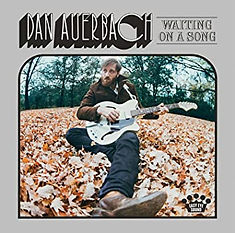

Album

Waiting on a Song

Artist

Dan Auerbach

Released

2017

Standout tracks

“Malibu Man”

“Shine on Me”

“Livin' in Sin”

Like the idea of folk music with a slightly cool sheen? Want to feel like you’re in late ‘60s Cali? Cue Dan Auerbach’s Waiting on a Song. The musician—best known as one half of the Black Keys—takes us on a mellow, melodic journey on his second solo album. There’s something honest, light-hearted, and simple about this record. It’s warm and lush in its production, and the horns add a subtle sunniness we can’t get enough of. While the Black Keys’ signature retro vibe is present, the album is firmly in its own lane. This makes sense considering the diverse range of musicians who played on it, including Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler and Nashville songwriter Luke Dick (responsible for tunes by Kacey Musgraves, Miranda Lambert, Dierks Bentley, etc).

Waiting on a Song is Auerbach’s follow-up to Keep It Hid, released in 2009.

D I V E I N

Notes from the Sea

There’s a temple a few minutes’ walk from my former island home in Hong Kong. It’s devoted to Tin Hau, the Empress of Heaven and Goddess of the Sea. Legend has it that, in a trance, she astral-projected herself to sea to save her father and brothers (all fishermen) from a typhoon. It’s said that when her mother woke her from her stupor, she dropped one of her brothers. The next day, he was the only family member not to return from sea. Since then, Tin Hau has been worshipped as the patron saint of fishermen, revered for protecting sea travellers from aquatic evils. But whenever I walked past the temple, I always wondered if there was a deity who could protect the sea from human evils.

* * *

It’s July 2021 and I’m paddleboarding on the South China Sea. The water’s placid but suddenly something knocks and rumbles against the underside of my board. The sensation is that of tyres rolling over an animal carcass in the road; jolting, terrifying, devastating. I quickly realise that, between water’s elasticity and the softness of my inflatable vessel, there’s no maimed animal. But I’m still terrified and devastated because I know that this disturbance is just as frightening. I turn towards the back of my board, anxiously waiting to see what pops out. It doesn’t pop so much as breach: a plastic detergent bottle, faded lilac in colour and about 30cm in height.

* * *

There’s something inherently sinister about imitation. A litany of colourful objects ride alongside my board and I can’t determine what is of the sea and what is in the sea. It’s only when I cautiously nudge it with the tip of my paddle that I see a piece of slick tree bark is in fact a single black rubber shoe. It’s as if plastic has assimilated simply by being there, where it doesn’t belong. It works; the ocean natives are fooled. I watch a small crab walk its body around a floating Coke can, an aluminium hamster wheel that makes no sense now he’s investigated it up-close. The sea and its inhabitants are now resigned to this specific breed of colonialism, rife with uncertainty, danger, and deceit.

Of course, not all of the trash I glide past is camouflaged. Much of it, too recent to have faded sufficiently into the tapestry of real life on the surface of the water, is quite clearly alien to this world. An orange plastic soda bottle completely in tact, too neon and buoyant to be natural. Lurid spidery residue of chilli sauce within a small plastic packet, resealed by the water pressure.

* * *

David Attenborough once said, ‘No one will protect what they don’t care about; and no one will care about what they have never experienced.’ Plastic pollution on beaches is not just an image to us; we experience it first-hand. We might be able to ignore third-world poverty or absolve ourselves of guilt about orangutans in Borneo, but when it comes to plastic floating around our children’s armbands and perching menacingly next to our unfurled towels, we have nowhere to hide.

Plastic on beaches: a line-up delivered by high tide, a modern art piece I don’t understand, a masterclass in artificial hue and indestructible form. It catches our eyes and sinks our hearts. It’s so incongruous with the natural surroundings of the beach and yet totally unsurprising to us now.

Where does it come from, all this stuff? People on boats, people on beaches, people far away who tossed something into the surf one day and watched it bob towards a place they couldn’t even see.

* * *

Last December, a few days before Christmas, there was a typhoon. It didn’t make direct landfall but it shook the trees outside our windows and closed our local shops for the day. When it was over, we walked to the beach. The post-typhoon sight included slim trees bent over, nature’s mulchy rubble strewn across the path, and synthetic trinkets of 2021, sat inanimate on the sand. There’s an unspoken rule within the community when it comes to keeping the island clean. Throughout the year, everyone does their bit to pick up the plastic from the beach. Some people are equipped with rubbish bags and rubber gloves and are at it before 8am. Others simply assess the situation when they get there and organise the plastic bottles by the nearby bin or fish lone items from the surf. After typhoons, there’s a larger crossover of helpers because there’s a larger amount to clean up; the best of humanity facing the worst of humanity, which has been washed up on shore for us all to see.

* * *

It’s not just plastic bottles and random singular items found on our beaches, though. Microplastics are tiny plastic particles less than five millimetres in size. Those that break off of larger pieces of plastic are known as secondary microplastics. Their detachment is usually a result of the sun’s radiation or general outdoor conditions. Primary microplastics are perhaps scarier. They come from commercial items we use daily and casually, like face exfoliators and fishing nets. Microplastics can be seen on beaches but are so tiny they’re hard to pick up and certainly aren’t as visible as hunks of plastic. Run a net through the ocean, though, and it’ll emerge full of the stuff, caught up in seaweed and other marine plants. Microplastics don’t break down easily or quickly (it can take hundreds of years for them to decompose), which means they typically end up on our beaches or in the stomachs of marine animals. Often, they end up in our stomachs, too. Research shows that microplastics have been found in seafood as well as drinking water.

* * *

Of course, there is no goddess who will save our seas from human sins. For better or worse, it’s us mere mortals who have been given the task (or, perhaps more fittingly, gift) of guardianship. The question, more pressing than ever, is: when will we step into the role?

R E A D S F O R W H E N E V E R

Four Thousand Weeks — Oliver Burkeman

Two things: (1) we humans (only) have roughly four thousand weeks on Earth; and (2) most of us are dissatisfied with aspects of our daily lives. Non-fiction read Four Thousand Weeks uses this information to tackle our issues around time management (productivity and busyness get a well-deserved slamming) and offer suggestions on how we can tweak our perspectives and beliefs to find more contentment in life. If you’re put off by the tagline (Time Management for Mortals), let us assure you: the book walks the perfect path between the practicality of time management and the emotional and mental approach we have towards living. Have a pencil and a (patient) person handy for all of the underlining and hey, did you know…’s.

R O O T S

Muscle

It may be hard to believe, but the words ‘muscular’ and ‘mousy’ are closely related. The Latin word for ‘muscle’ (musculus) also means ‘little mouse’. The reason for the double meaning comes from the way some muscles, especially biceps, move under the skin when flexed, like little scuttling mice. The same connection was made by the Greeks (mys refers to both mice and muscles). In the 1800s, we came to understand ‘muscle’ as brawn or strength, and in the 20th century, the definition of ‘muscle’ expanded further with the use of ‘muscle car’, which refers to powerful American sports cars of the ‘60s.